Sludge treatment − how does anaerobic digestion work?

How anaerobic digestion works

Anaerobic digestion (AD) is used to both stabilise sludge, i.e. reduce its odour, putrescence (tendency to decay) and pathogenic bacteria content, and convert the solids to a useful, combustible gas product (a biogas). This is achieved by biological degradation of the organic matter in the absence of oxygen to generate methane as the main product, rather than carbon dioxide as in the case of aerobic digestion.

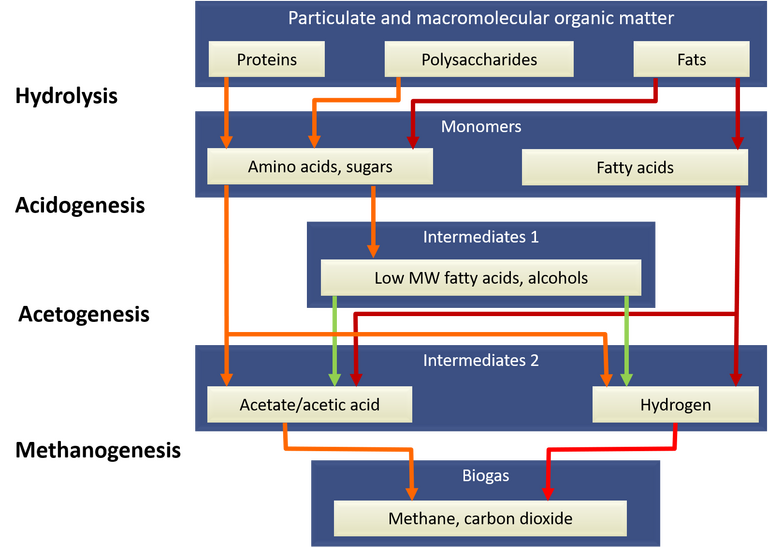

AD is essentially a multi-step process comprising:

- hydrolysis (reaction with water to convert large organic molecules to smaller ones),

- acidogenesis (conversion of small organic molecules to volatile fatty acids),

- acetogenesis (conversion of volatile fatty acids to acetic acid and mineral products), and finally

- methanogenesis (conversion of organic molecules to methane).

The first three steps concern the breakdown of large organic molecules to smaller ones, and specifically acetic acid. In the final step, methane is generated.

In the initial hydrolysis step, acid-forming bacteria hydrolyse macromolecular (i.e. large molecules) organic materials such as proteins, polysaccharides and lipids, breaking them down into smaller water-soluble molecules like sugars, amino acids and glycerol. These simpler molecules are then degraded by acidogenesis to form volatile fatty acids (VFAs), or low-molecular weight organic acids, along with hydrogen and carbon dioxide.

In the third step, acetogenesis, the VFAs are further oxidized to hydrogen, carbon dioxide and acetate. This is followed by the fourth step, methanogenesis, which is the bacteriological generation of methane. Methane can be generated via two routes, either from hydrogen and carbon dioxide (by hydrogenotrophic bacteria), or from acetate (by acetotrophic bacteria).

The hydrogenotrophic bacteria feed off the hydrogen generated by the acetogenic bacteria in the preceding step. This maintains the hydrogen at a sufficiently low level to promote acetogenesis − as the hydrogen is used up to form methane, it is replaced by the conversion of acetate to more hydrogen. Acetotrophic bacteria feed off acetate.

The complete biochemical mechanistic pathway is very complex. It features synotrophy − a kind of biochemical symbiotic relationship − between the methanogenic bacteria and other partner microbes present. The partner microbes are able to cooperate in bringing about the conversion of the organic matter to biogas. They oxidize liquid products of acidogenesis to acetate, carbon dioxide, hydrogen and formate, and these are then in turn directly used by the methanogens to generate methane.